I’m just in the middle of studying the use of meta-learners for causal inference, i.e. how to repurpose conventional ML models to estimate treatment effect. One of the lessons I took away from this study so far is that no matter how fancy the ML algorithm we use, without a plausible model of the data-generating process, we cannot hope for an unbiased estimate of the treatment effect as without it, it is difficult to select relevant covariates and avoid those that introduce bias into our estimation (e.g. colliders, mediators and their descendants).

To illustrate and reinforce this lesson for myself, I coded a small example of estimating the average treatment effect of training performance on productivity using synthetic data with a known data-generating process and the Double ML method.

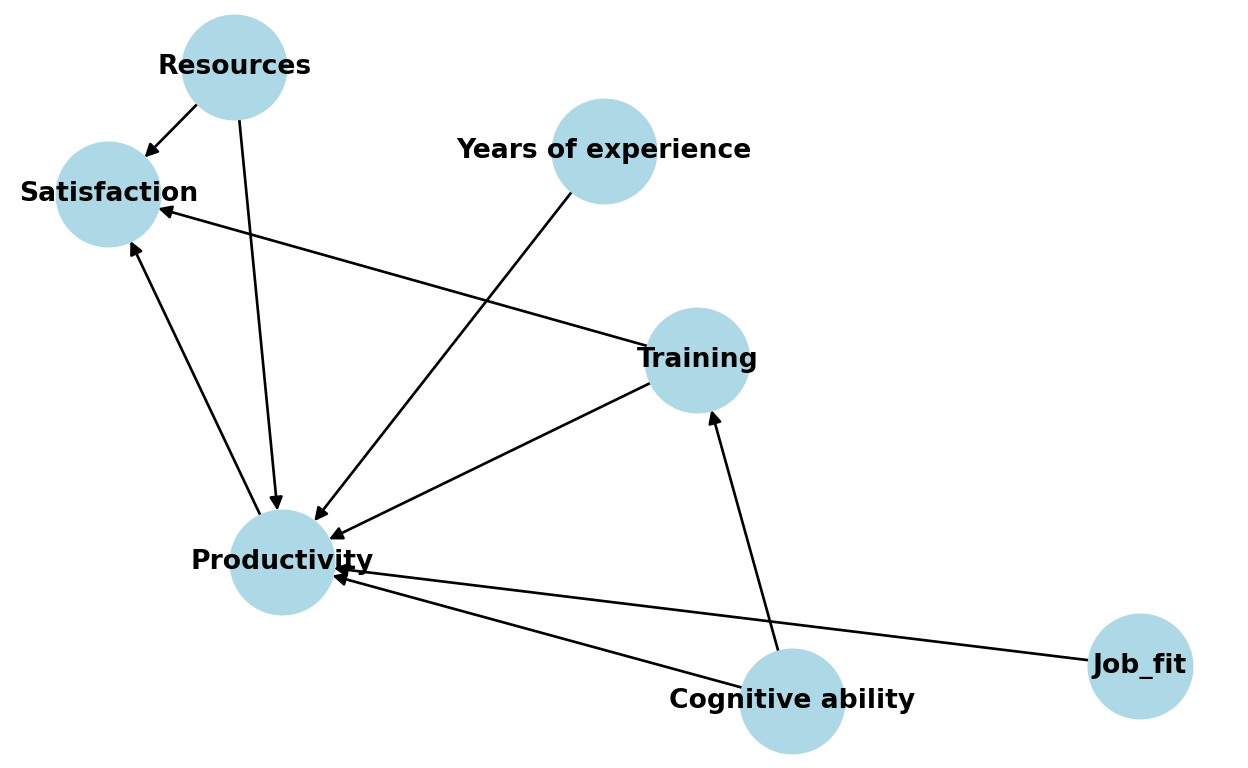

First, we create a DAG of the causal relationships behind our data. We see that, according to this DAG, employee productivity is affected by years of experience, job fit, available resources, and training performance, which is our variable of interest. Employee satisfaction is also part of the DAG, which is affected by available resources, employee productivity, and training performance.

Show code

import networkx as nx

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# initializing DAG

G = nx.DiGraph()

# adding nodes

nodes = ['Years of experience', 'Resources', 'Job_fit', 'Training', 'Productivity', 'Satisfaction', 'Cognitive ability']

G.add_nodes_from(nodes)

# adding edges

edges = [('Years of experience', 'Productivity'),

('Cognitive ability', 'Productivity'),

('Cognitive ability', 'Training'),

('Resources', 'Productivity'),

('Resources', 'Satisfaction'),

('Job_fit', 'Productivity'),

('Training', 'Productivity'),

('Training', 'Satisfaction'),

('Productivity', 'Satisfaction')]

G.add_edges_from(edges)

# drawing DAG

pos = nx.fruchterman_reingold_layout(G, seed=5, iterations = 500, k = 2)

labels = {node: node for node in G.nodes()}

nx.draw(G, pos, with_labels=True, labels=labels, node_color='lightblue', font_weight='bold', node_size=1500, font_size=10)

plt.title("DAG")

plt.show()

Now let’s generate synthetic data corresponding to this DAG.

Show code

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

# generating synthetic data

np.random.seed(42)

n = 1000

# generating features years of experience, resources, job fit, and cognitive ability

X = np.random.normal(0, 1, (n, 4))

# setting the true causal effect of training performance

true_causal_effect = 3.5

# training is influence by cognitive ability

training = 1.8 * X[:, 3] + np.random.normal(0, 1, n)

# productivity is influenced by all features

productivity = 2 * X[:, 0] + 1 * X[:, 1] + 0.5 * X[:, 2] + 2.2 * X[:, 3] + true_causal_effect * training + np.random.normal(0, 1, n)

# defining an employee satisfaction variable that is influenced by resources, productivity, and training

satisfaction = 0.3 * X[:, 1] + 0.2 * productivity + 1.3 * training + np.random.normal(0, 1, n)

# creating a final dataFrame

df = pd.DataFrame(X, columns=['years_of_experience', 'resources', 'job_fit', 'cognitive_ability'])

df['training'] = training

df['productivity'] = productivity

df['satisfaction'] = satisfaction Without DAG, i.e., without understanding the data-generating process behind our data, we might be tempted to “throw” all available variables into our estimator. We can give it a try and use Double ML for that - a popular framework designed to provide unbiased and consistent estimates of treatment effects in the presence of high-dimensional controls while reducing the risk of overfitting. The common Double ML procedure looks as follows:

- Randomly splitting the data into two parts: one for estimating the control function and the other for estimating the treatment effect.

- Using the first part of the data to train a machine learning model to predict the outcome variable based on covariates (without the treatment variable). Similarly, training another model to predict the treatment variable based on covariates.

- Using the second part of the data to form the residuals for outcome and treatment variable and running a simple linear regression of outcome residuals on treatment residuals.

- Repeating steps 1-3 but switching the roles of the two data splits and averaging the estimates to get the final average treatment estimate.

Let’s apply this approach to our data and use XGBoost models to estimate the control function and see how successful we will be in our efforts to estimate the known causal effect of training on productivity.

Show code

import numpy as np

from xgboost import XGBRegressor

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

# creating a variable for data splits

np.random.seed(42)

df['part'] = np.random.choice([0, 1], size=len(df))

estimates = []

for p in [0,1]:

# auxiliary variables for switching the roles of the two data splits

firstPart = 1-p

secondPart = p-0

# used covariates

covariates = ['years_of_experience', 'resources', 'job_fit', 'cognitive_ability', 'satisfaction']

# preparing datasets

X_First = df.loc[df['part'] == firstPart, covariates].values

y_Outcome_First = df.loc[df['part'] == firstPart,'productivity'].values

y_Treatment_First = df.loc[df['part'] == firstPart,'training'].values

X_Second = df.loc[df['part'] == secondPart, covariates].values

y_Outcome_Second = df.loc[df['part'] == secondPart,'productivity'].values

y_Treatment_Second = df.loc[df['part'] == secondPart,'training'].values

# controlling for covariates for productivity using XGBoost

model_Outcome = XGBRegressor(eta = 0.1, n_estimators =25)

model_Outcome.fit(X_First, y_Outcome_First)

residual_Outcome = y_Outcome_Second - model_Outcome.predict(X_Second)

# controlling for covariates for training using XGBoost

model_Treatment = XGBRegressor(eta = 0.1, n_estimators =25)

model_Treatment.fit(X_First, y_Treatment_First)

residual_Treatment = y_Treatment_Second - model_Treatment.predict(X_Second)

# Part 3: Estimate the causal effect using the residuals with Linear Regression

model_causal = LinearRegression()

model_causal.fit(residual_Treatment.reshape(-1, 1), residual_Outcome)

double_ml_effect = model_causal.coef_[0]

estimates.append(double_ml_effect)

LinearRegression()In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

LinearRegression()

Show code

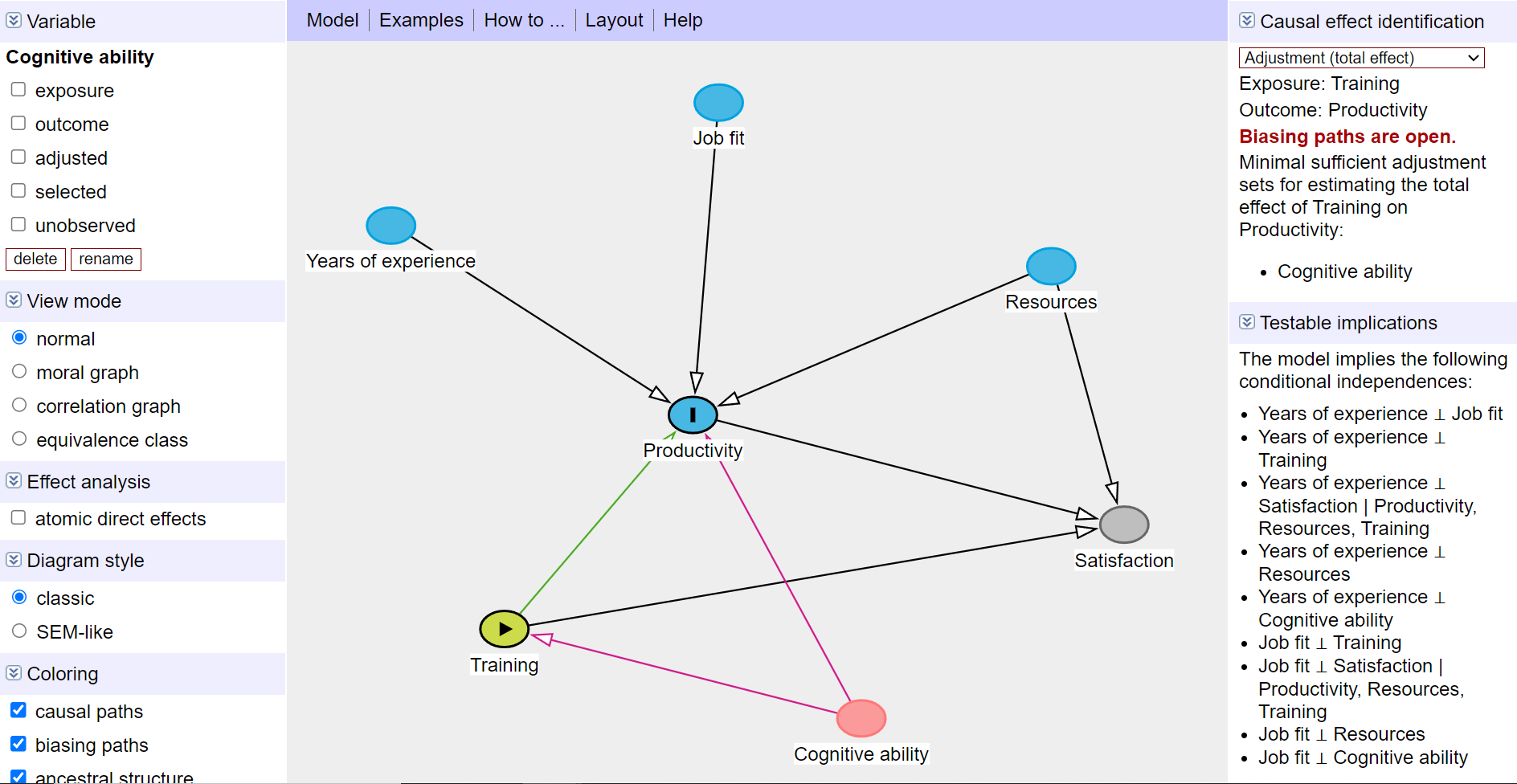

print("The estimated Average Treatment Effect is:", sum(estimates)/len(estimates))The estimated Average Treatment Effect is: 2.8913607224732614We see that the estimated causal effect of training is approximately 2.9, quite far from the known value of 3.5. How so? Well, if you look at the DAG above, you can see that by using all the variables as covariates, not only have we correctly blocked the backdoor by controlling for employee cognitive ability, but we have also introduced bias into our estimation by controlling for satisfaction, which is a collider - a variable that is affected by both the outcome (productivity) and the treatment (training). And controlling for colliders leads to spurious correlations between variables or, as in our case, deflates the size of the estimated effect. We can easily check this using DAGitty, which is a wonderful browser-based environment for creating and analysing causal diagrams.

So let’s repeat the estimation, but now without satisfaction variable as covariate. As you can see below, we are now much closer to the actual causal effect.

Show code

# creating a variable for data splits

np.random.seed(42)

df['part'] = np.random.choice([0, 1], size=len(df))

estimates = []

for p in [0,1]:

# auxiliary variables for switching the roles of the two data splits

firstPart = 1-p

secondPart = p-0

# used covariates

covariates = ['years_of_experience', 'resources', 'job_fit', 'cognitive_ability']

# preparing datasets

X_First = df.loc[df['part'] == firstPart, covariates].values

y_Outcome_First = df.loc[df['part'] == firstPart,'productivity'].values

y_Treatment_First = df.loc[df['part'] == firstPart,'training'].values

X_Second = df.loc[df['part'] == secondPart, covariates].values

y_Outcome_Second = df.loc[df['part'] == secondPart,'productivity'].values

y_Treatment_Second = df.loc[df['part'] == secondPart,'training'].values

# controlling for covariates for productivity using XGBoost

model_Outcome = XGBRegressor(eta = 0.1, n_estimators =25)

model_Outcome.fit(X_First, y_Outcome_First)

residual_Outcome = y_Outcome_Second - model_Outcome.predict(X_Second)

# controlling for covariates for training using XGBoost

model_Treatment = XGBRegressor(eta = 0.1, n_estimators =25)

model_Treatment.fit(X_First, y_Treatment_First)

residual_Treatment = y_Treatment_Second - model_Treatment.predict(X_Second)

# Part 3: Estimate the causal effect using the residuals with Linear Regression

model_causal = LinearRegression()

model_causal.fit(residual_Treatment.reshape(-1, 1), residual_Outcome)

double_ml_effect = model_causal.coef_[0]

estimates.append(double_ml_effect)

LinearRegression()In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

LinearRegression()

Show code

print("The estimated Average Treatment Effect is:", sum(estimates)/len(estimates))The estimated Average Treatment Effect is: 3.477088075986001Despite the simplicity of the example presented, I think it nicely demonstrates that by using fancy ML algorithms like XGBoost, we are not relieved of the need to have a plausible model of the data-generating process when estimating causal effects from observational data, and we can’t just blindly rely on some magical powers of ML to squeeze what we need out of whatever input we give it.

Just a side note: If you want to make your life a little bit easier when using Double ML, you can use the DoubleML library for Python and R. The code below illustrates this library in action on our synthetic data.

Show code

from doubleml import DoubleMLData, DoubleMLPLR

np.random.seed(42)

# specifying data and roles of individual variables

dml_data = DoubleMLData(df, y_col='productivity', d_cols='training', x_cols=['years_of_experience', 'resources', 'job_fit', 'cognitive_ability'])

# specifying ML model(s) used for estimation of the nuisance parts

ml_xgb = XGBRegressor(eta = 0.1, n_estimators =25)

# initializing and parametrizing the model object which will be used to perform the estimation

dml_plr_xgb = DoubleMLPLR(

dml_data,

ml_l = ml_xgb,

ml_m = ml_xgb,

n_folds = 5,

n_rep = 10,

score = 'partialling out',

dml_procedure = 'dml2')

# estimation and inference

dml_plr_xgb.fit()<doubleml.double_ml_plr.DoubleMLPLR object at 0x000001A9267BACE0>Show code

dml_plr_xgb.summary coef std err t P>|t| 2.5 % 97.5 %

training 3.426416 0.049597 69.085291 0.0 3.329208 3.523624Show code

dml_plr_xgb.confint() 2.5 % 97.5 %

training 3.329208 3.523624